Home is where the resiliency is

Empowering communities to thrive in a warming world.

The climate crisis is often presented abstractly. When you plot annual global temperatures on a graph and connect the dots, you see an upward tilting curve, but with its fraction-of-a-degree intervals, these subtle shifts can be hard to connect to everyday life.

Meanwhile, unprecedented heatwaves, wildfires, and ice storms are staring us in the face from our own backyards--an ever-present reminder that a degree or two increase in the global average translates to local variations that can be devastating for those living in affected areas.

According to a report published by Multnomah County, Oregon, there were 72 heat deaths in the county in 2021, 69 of which resulted from a single heat dome when the temperature soared 35 degrees above the historic average. Today, similar extreme heat events occur nationwide. A report by the National Weather Service from the same year saw heat-related fatalities topping any other cause by a large margin. But as dangerous as extreme temperatures can be, heat alone is often not the culprit. Our building stock—woefully underprepared for today’s climate, let alone the more extreme climate of the future—contributes to these avoidable deaths.

Some of us are more insulated from the realities of the climate crisis than others—literally. Underserved communities tend to suffer more from extreme weather events, including extreme heat. As demonstrated by this New York Times mapping exercise, redlined neighborhoods, which remain poorer and more likely to have minority residents, are some of the hottest parts of town due to an abundance of heat-trapping pavement and few, if any, trees. These areas also tend to have lower-quality buildings that struggle in extreme conditions, while the more well-off and tree-lined neighborhoods stay significantly cooler. According to the Multnomah County report referenced above, those living in multifamily buildings or in the hottest (poorest) parts of the city were disproportionately killed by the heat dome.

Practical passive design strategies

Affordable housing sits at the intersection of the outlined challenges and the opportunity to address them. Following the 2021 heat dome, the Portland Housing Bureau began to mandate cooling—a positive development, but only part of the picture. Passive building design strategies can more proactively help mitigate health risks related to heat and maintain safe conditions. Better insulation and air sealing slow heat transmission into living units during the day and minimize the capacity (and cost) of mechanical systems necessary to maintain comfort. Climate change is also shifting rainfall and snowmelt patterns, which is stressing the region’s hydro-based electrical grid. Climate resilience must consider what happens when the power goes out.

The 2021 heat dome compelled us to peer into the future to fully understand what we are designing for. It also prompted more effective communication of climate risks and a better understanding of the mitigating strategies that will keep people safe. By splicing climate data from the week of the heat dome into weather files used to study our buildings, our team can now evaluate how a design would perform during a similar future event. Testing housing projects during a heat-wave-without-power scenario gives us the tools to create resilient buildings in a warming world.

The Legin Apartments at Portland Community College (PCC)’s Southeast Campus, bringing 124 units over four stories to Portland’s Montavilla neighborhood, were designed by Bora Architecture & Interiors with this approach. Scheduled to open in 2026, the project will offer a model for resilient affordable housing design in climates that are new to extreme heat. Among the performance goals of the project is the vision to create a future-proof building that adapts to changing climatic conditions and occupant needs through anticipatory design. This was our first project to be tested against the heat dome and the lessons are already informing designs across our portfolio.

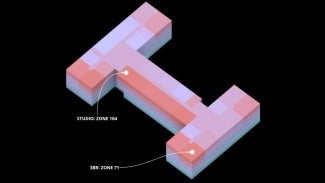

For this project we studied the indoor temperature of every unit over the three-day heat dome, and the days following, without active systems. A large variation exists between units based on orientation and level, and special focus was placed on the most vulnerable cases: west-facing, top-floor units which would see the largest solar heat gain throughout the day (Fig. 1).

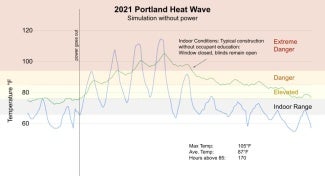

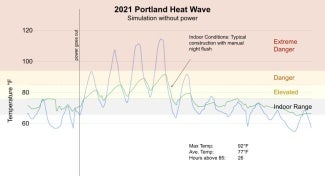

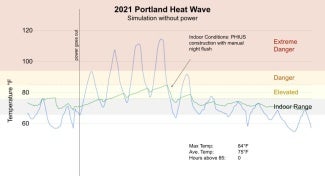

The study charted indoor air temperatures for these worst-case units under the following scenarios:

Baseline Scenario: Code-minimum construction without occupant input in which blinds remain open throughout the day and operable windows remain closed at night (Fig 2).

Engaged Occupant Scenario: Code-minimum construction, but with occupant input in which the shades are lowered during the day and windows are open at night (Fig 3).

Advanced Construction Scenario: Adding continuous exterior rigid insulation, low-e double-pane glazing, and tight air sealing, with the same engaged occupant input as above (Fig 4).

The Baseline Scenario (Fig 2) pushes into the “extreme danger” range and temperatures remain dangerously high over the following week as accumulated heat has no way to escape. Comparing this outcome to the next scenario (Fig 3), the same building, this time with an educated and engaged occupant, has remarkable capacity for well-controlled shading and natural ventilation to eliminate “extreme danger” temperature hours altogether. Looking at the same occupant behavior, but coupled with advanced construction (Fig. 4), the number of hours above 85 degrees is reduced to zero, shielding occupants from exposure to “dangerous” conditions.

These results highlight the potential of straightforward design strategies to achieve passive survivability in multi-family housing. The Legin Apartments leveraged these studies in both design and communication and incorporated architectural and behavioral strategies that were demonstrated to have a meaningful impact. A quality enclosure, coupled with night venting and occupant education, keeps living spaces habitable. This illustrates the concept of passive survivability--the ability to safely shelter in place without power. While temperatures might fall outside of ideal thermal comfort ranges, when a space is designed and operated correctly, hazards can be avoided. The added benefit of designing for resilience through passive survivability is that the same strategies that protect people during heat waves and power outages will make for more comfortable, healthy, and energy-efficient spaces year-round.

Architects and designers have the unique opportunity to address looming climate challenges in a tangible way by implementing the following proven design strategies and engaging with housing providers and occupants to ensure they understand how to effectively operate shades and windows.

- Select windows with low solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) and keep window-to-wall ratios in check, particularly on west-facing facades

- Provide and locate operable windows to maximize night flushing potential during cool night hours

- Choose a massing design that minimizes envelope area or provides self-shading

- Provide exterior and/or interior shading for glazed openings

- Choose exterior roof finishes and colors with a high solar reflective index (SRI)

- Provide continuous insulation and air barrier around the thermal envelope and properly air seal

A home is a shelter from the elements and a place of respite from the outside world. But as we continue to face climate uncertainties, it is becoming increasingly apparent that we must broaden this definition and design for its implications: a true home is where the resiliency is.

The Legin Apartments was developed in collaboration with Portland Community College, Our Just Future, and Edlen & Co.

Thuy Le, AIA, is an associate at Bora Architecture & Interiors in Portland, Ore., with experience on a wide range of project types, including libraries, workplace, affordable housing, and K-12 education. As an advocate for resilient architecture and evidence-based design, she has been a driving force behind Bora’s highest-performing projects.

Corey Squire, AIA, is the sustainability director at Bora Architecture & Interiors in Portland, Ore., and a member of the American Institute of Architects' Strategic Council. He is the author of the recently published book People, Planet, Design: A Practical Guide to Realizing Architecture’s Potential.