Will the 2025 economy improve for architects?

AIA Chief Economist Kermit Baker says firms think that the economy needs to course-correct before their workloads can rebound.

From a business perspective, most U.S. architecture firms faced a challenging year in 2024, according to data from the AIA/Deltek Architecture Business Index (ABI).

Continuing the weakness that emerged mid-year 2023, architecture firms reported the softest period of billings since the onset of the pandemic in early 2020. Conditions began to look a bit more positive beginning in the fourth quarter of last year as commercial property values stabilized, interest rates began to edge down, and architecture firms began to report a resurgence in interest in new design projects.

However, this optimism is not uniform; many firms still feel that additional corrections in the economy are needed before their workloads will rebound. When surveyed this past October about revenue forecasts for 2025, just over four in ten firms were projecting gains of 5% or more, a quarter were projecting losses of that magnitude, while a third felt revenue would be essentially flat. Larger firms, firms specializing in the institutional sector, and firms located in the South were the most optimistic about their expected 2025 performance.

However, even though the design cycle may be bottoming out and beginning to turn the corner, there are more than the usual number of risks to the outlook for the industry. Some of the risks are on the upside, suggesting that 2025 may turn out better than expected, while others are on the downside. A recent survey by Equipment World magazine polled construction executives as to what policy changes would have the biggest impact on their business. Of the four most common responses, two were thought to have a positive impact on their performance—a rollback in environmental regulations and interest rate cuts. Two, however, were thought to have a negative impact—potential for increased tariffs, and stricter immigration policies.

Roll back on environmental regulations: Contractors have long complained about growing federal environmental regulations for construction. The incoming Trump administration has expressed the desire to streamline this process. Additionally, the new administration has pledged expedited approvals and permits on projects for companies that invest in megaprojects valued at $1 billion or more. However, most of the regulation of construction projects occurs at the municipal level, and it will be more challenging to ease state and local building codes and regulations to spur more construction.

Interest rate cuts: Though promising to bring down stubbornly high interest rates, the Trump administration has limited ability to make that happen. Short-term rates are largely set by the Federal Reserve Board, and long-terms rates by investors based on where they feel inflation is headed. Bringing down interest rates, therefore, would largely depend on developing strategies to hold down inflation.

Potential for increased tariffs: The threat of increased tariffs is a major source of concern regarding reigniting inflation. The threatened 25% tariffs on goods imported from Canada and Mexico and an additional 10% tariffs on good imported from China would be inflationary to the overall economy since they are our three largest trading partners. Also, these tariffs could limit the availability of several materials and products used in construction. Among other products, the industry imports lumber and construction equipment from Canada, cement and gypsum from Mexico, and furniture, plastics and electronics from China.

Stricter immigration policies: Perhaps the biggest concern to the construction industry is how the construction labor force might be impacted by emerging immigration policy. There are approximately 12 million construction workers nationally, of which about three million are foreign born. It is estimated that half of these immigrants are undocumented, so it is likely that about one in eight construction workers nationally is undocumented. The concern is not only the potential deportation of undocumented workers, but also the chilling effect on potential new immigrants who might fill construction positions in coming years.

Construction spending is slowing, except for the manufacturing sector

The U.S. building construction market has been on a tear in recent years. Spending on commercial, industrial, and institutional facilities dipped modestly in 2021 before increasing 18% in 2022, another 19% in 2023, and a more modest 6% estimated for this past year. While the performance of the industry over the past three years has been extremely impressive, it also has been unusually unbalanced.

Three niche sectors in the industry—manufacturing, warehouses, and data centers—accounted for a third of all construction spending in the commercial, industrial, and institutional sectors in 2022, and that share rose to almost 40% in 2023 and again in 2024. Spending on manufacturing facilities has seen a meteoric rise, accounting for well over a quarter of all building spending last year. In fact, ignoring the manufacturing sector, spending on nonresidential buildings increased a more modest 12% in 2022, 11% in 2023, and less than 2% last year.

Much of the increase in manufacturing has been attributed to reshoring activity. International supply chains were overwhelmed during the pandemic, encouraging U.S. producers to increase their domestic production. While this no doubt was a factor in boosting domestic manufacturing construction activity, it’s an incomplete explanation. Reshoring as a motivation for increased domestic manufacturing construction would suggest that most sectors of the economy would be involved in increasing their domestic capacity. What we see instead is that a few sectors dominate manufacturing construction. In 2023, of the almost $200 billion in manufacturing construction spending in the United States, fully a third of it was for computer and electronics production, while an additional quarter was to produce chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Most, however, was spent to produce plastics. The surge in plastics production largely stems from increased domestic production of oil and gas, which are key inputs.

Other than the surges in construction for manufacturing, warehouse, and data center facilities, most other sectors have seen much more modest levels of activity in recent years. Last year, construction spending declined for the retail and other commercial sector, as well as for lodging. Spending on offices saw a very modest increase only because the U.S. Census Bureau classifies data centers in the office category. The major institutional sectors fared a bit better, with spending on health care and education both increasing in the 5% to 10% range.

Construction starts pointing to a 2025 slowdown

Construction starts—where the entire projected value of a project is assigned to the month when construction begins and is therefore a leading indicator of construction spending—points to a continued slowdown in construction spending over the coming 12 to 18 months. Total nonresidential building starts declined in 2024 according to ConstructConnect, a firm tracking construction project leads. Commercial sector starts were up at a low single-digit pace percentagewise over 2023 levels, while institutional starts were up at a high single-digit pace. However, the big change was that starts for manufacturing facilities fell precipitously.

Commercial sector starts were up at a low single-digit pace percentagewise over 2023 levels, while institutional starts were up at a high single-digit pace. However, the big change was that starts for manufacturing facilities fell precipitously.

Forecasters predicting only very modest growth this year and next

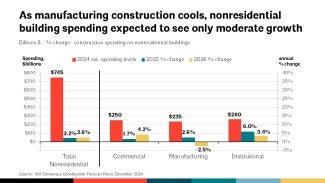

The most recent AIA Consensus Construction Forecast Panel projects only very modest gains in construction spending this year and next. Total nonresidential building spending is projected to increase a mere 2.2% this year before modestly rising to 2.6% in 2026. Those gains likely won’t even offset increases in material and labor costs, so the expectation is that the volume of construction is not expected to increase over the coming two years.

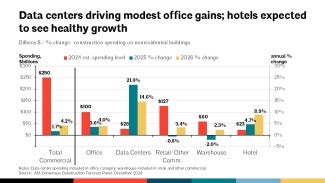

Within the commercial sector, spending on offices is expected to increase modestly this year and next. Spending on retail and other commercial facilities is expected to see no gains this year before a modest uptick in 2026, with hotels expected to see mid-single-digit growth this year and high single-digit growth next year.

The projected increase in spending on offices might seem surprising given the high levels of remote work which has produced high vacancies in office spaces, growing pressure on rents, and overall weakness in that market. However, all of the projected increase is coming from data centers, which the Census Bureau includes in the office category. Spending on data centers is projected to continue to see very strong growth, so spending in the core office category is expected to decrease both this year and next.

Retail and other commercial facilities have been hurt by the growth in e-commerce. The Census Bureau includes warehouses in this category, and that has driven overall category growth in recent years. However, warehouse construction has become overbuilt in many areas of the country in recent years, and therefore construction spending in this sector has slowed.

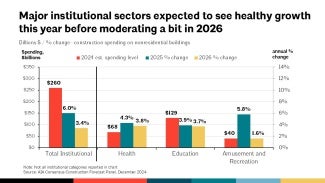

Institutional building tends to be less cyclical than commercial or industrial activity and is therefore less prone to a boom/bust pattern. The major institutional sectors—healthcare and education—are both poised for healthy but unspectacular gains this year and next. Healthcare construction has benefited from an aging population. Consolidation among healthcare providers has changed the construction focus away from large institutional campuses and toward neighborhood health centers.

Education is the largest institutional category, accounting for over a third of the spending on institutional facilities. In addition to some upgrading of facilities that was deferred during the pandemic, demographics are the main driver of educational construction needs. As such, moving forward, construction spending for education facilities is likely to be under pressure. The Census Bureau projects our overall population to increase by 2.1% in total over the next five years. However, the preschool population is projected to increase only 0.7%. Meanwhile, the elementary school population is projected to decline by 4%, high schoolers by just over 3% and college-aged students by almost 2%. Those trends are expected to limit the need for new educational facilities.

Kermit Baker, Hon. AIA, is AIA's Chief Economist and a Senior Research Fellow at Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies.