Accounting basics: The income statement & KPIs

Contributed by Michael A. Webber, All. AIA, A/E Finance

Chapter 7.02

Learn the basics of accounting for architecture firms relating to the Income Statement, or Profit & Loss Statement—including certain industry-standard KPIs that are essential to monitoring firm operations and managing firm profit.

Basic categories of revenue & expense

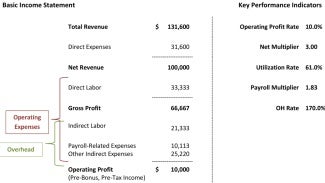

The income statement has only one category in which to record revenue and four categories in which to record expenses. Of the expense categories, there is a differentiation between direct (project-related) and indirect expenses, and, within each of these, a differentiation between labor- and non-labor-related expenses. As a result, the broad categories on an income statement are direct expenses, direct labor, indirect expenses, and indirect labor. Subtract these labor costs and expenses from revenues, and the amount remaining is called operating profit—the pre-bonus, pre-tax profit or loss a firm derives from its operations.

A very rudimentary income statement is included here to show how and where each category fits. The numbers are representative of long-term historic industry averages. Nonetheless, a big "±" sign should precede each number, as actual amounts vary quite significantly from firm to firm and year to year.

Revenues

Revenue is nothing more complicated than the invoices a firm sends to its clients. Each project’s invoices are recorded separately and the sum of them is the firm’s total revenues. However, there usually are charges on invoices for more than just the fees for services the firm itself provides.

Projects usually have engineering consultants—structural, civil, MEP, etc.—working on the project through the architect’s contract whose fees also have to be included on the invoice. In addition, there may be any number of other expenses included in the invoice. In fact, consultant fees and other expenses can be 40% or more of total fees. These types of project-related expenses are the first expense category.

Direct expenses

"Direct" refers to any expenses a firm incurs because of a project. There are both direct expense and direct labor categories. Direct expenses are all non-payroll-related expenses the architect incurs specifically because of a billable client project. Direct expenses include all engineering and other consultants hired to work on a project. There also are a myriad of other expenses directly related to a specific project, such as testing and lab costs, travel expenses, copying, printing, and shipping charges.

Direct expenses include both reimbursable and non-reimbursable expenses. Just because an expense incurred for a project is not specifically reimbursable according to a contract does not mean that it is not a direct expense. For example, there is no difference between a contract for $450,000 that has $50,000 of reimbursable expenses, and a contract for $500,000 that has $50,000 of non-reimbursable expenses.

Whether itemized or not, these expenses are included in invoices to clients and paid from the revenues collected. However, because direct expenses are not incurred except for projects, they are not part of a firm’s overhead or operating costs.

Net revenues

Net revenue is as much a concept as it is a number essential for understanding any architectural firm’s finances. In fact, net revenue is a more important number to a firm than total revenue. While net revenue is simply total revenue minus total direct expenses, it is more important to recognize that a firm’s net revenue is the money it needs to generate to be able to pay its employees and its other expenses, and, hopefully, produce profits.

Net revenue, not total revenue, is what a firm needs to forecast, budget, and track—on a project-by-project and department-by-department basis—and it can because industry accounting packages are project-based. Moreover, it is the amount and changes in total net revenue that reflect a firm’s growth or decline, not total revenue.

Operating expenses

As discussed, the net revenues that appear on an income statement are recognized as that firm’s funds from which it pays its own expenses. As such, a firm’s operating expenses encompass the remaining three expense categories. In the example income statement, operating expenses, which are net revenue minus operating profit, total $90,000.

Net revenue can—and should—be calculated for each project, PM, department, and division, as well as for the firm as a whole, as it represents the amount of net revenue a project, PM, department, and division earns a firm for its services.

Direct labor

A firm’s own people provide the services that generate net revenue, so the next category is direct labor. Direct labor costs are the actual wages paid to people for all hours spent working on a client project, and each direct labor hour is recorded for a specific project at each individual’s standard pay rate.

For example, if a person is paid $1,000 for a standard 40-hour workweek, that person’s standard cost rate is $25.00 per hour. If that person works 5½ hours on a specific project, that project incurs a direct labor charge of $137.50. Regardless of whether or when these hours actually are billed to a client, the project and the firm have incurred these direct labor costs.

Overhead

As mentioned, there are two "direct," that is, project-related, expense categories: this direct labor category and the previous direct expense category. Together they represent the actual costs incurred in providing client project services. What remains are the two indirect expense categories. More frequently referred to as overhead, indirect expenses are better recognized as ongoing expenses of running a firm, including marketing, administrative, and other non-project staff time; employee taxes and benefits; and facility, corporate, and non-labor marketing costs.

Indirect labor

Within all A/E firms, there always is a focus on project (direct) time. However, there is a significant amount of time that goes towards non-project-related (indirect) activities, some of which may not be obvious. First, there is vacation, holiday, sick, etc., time that all staff receive as a benefit. There also is a considerable payroll for support staff: people not hired to work on projects, but rather to handle accounting, administrative, HR, and marketing functions.

In addition, there are significant amounts of time that professional staff spend on necessary and appropriate, but non-project-related activities. Consider the great amount of professional time dedicated to marketing and business development. Professional staff also need to attend conferences, seminars, webinars, and training courses for individual or firm-wide continuing education needs. Last but not least, there is the undesirable "I-do-not-have-a-project-to-work-on" time that all staff and firms seek to avoid. Finally, there is the time spent by management staff on administrative and organizational tasks and responsibilities related to managing a firm.

Indirect expenses

Indirect expenses are the last of the four expense categories: the two direct and indirect categories; each further separated into a labor and an expense category. This structuring is quite helpful because the total direct expenses on all client projects have to reconcile with the direct expense accounts on the income statement; the two labor categories on the income statement, when added together, have to reconcile with the firm’s payroll system; and the indirect expense category is, literally, "everything else."

However, rather than "everything else," indirect expenses are more easily explainable and understandable if the category is viewed as having two components, one of which is quasi-labor related.

Payroll-related indirect expenses

In addition to whatever wages or salaries a firm pays its people, all firms need to pay mandatory federal and state payroll and unemployment taxes each payroll period. Also, a firm’s general liability and workers’ compensation insurance premiums are related to each firm’s total payroll. Further, most firms also provide employee benefits, such as health and life insurance programs, pension or 401(k) contributions, etc.

Consider these expenses as payroll-related because the actual expense amounts vary proportionately to total employee and payroll levels—and they are significant.

Historically, payroll-related expenses add 15–20% of a firm’s total salary and wage costs.

Before going to the final indirect expense component, it is appropriate to refer back to the example income statement and numbers therein. As diagrammed, direct and indirect labor are the first two components of operating expenses, and as just discussed, there is a breakout of payroll-related expenses. All three are a firm’s people-related expenses, and, recognizing that the numbers are averages, they demonstrate that the cost of people can be 70–75% of total operating expenses. That should be no surprise because architecture is part of the professional services industry, and as such, it is the hours and talents of people that architecture firms sell to clients. In this business, a firm saying "Our people are our most important asset" is no cliché.

Other indirect expenses

This final component of indirect expenses comprises all of a firm’s not-yet-discussed expenses. Grouped into four major categories, these include:

· Facility expenses: Rent, utilities, and maintenance costs; telephone and other communication costs; computer equipment, software, licenses, and supplies; office supplies; depreciation, which is how a firm recoups all its investments in furniture and furnishings, leasehold improvements, and vehicles.

· Other staff expenses: Professional registrations and dues; conferences, seminars, and other training fees; recruiting expenses; non-marketing-related travel and meals.

· Corporate expenses: Professional liability and other insurances; legal and accounting fees; other general administrative expenses.

· Non-salary-related marketing expenses: Websites, photographs, brochures, and proposal materials; marketing-related travel expenses; client meals and entertainment.

One last note about other indirect expenses: Yes, somewhat surprisingly, all of these may constitute only 25–30% of a firm’s total operating costs. However, several specific and large line items, such as rent and professional liability insurance, are only negotiated once a year or less, and depreciation is fixed because it is based on past investments. The same is true for specific and large payroll-related expense line items, such as health insurance policies, which usually are an annual issue, and payroll taxes, which are not even negotiated.

This means that most of the total other indirect expense overhead expenses are not controllable day-to-day. That is not to say that these costs are not significant and that management need not pay attention to them. Rather, it indicates that, by far, the most monitorable and manageable overhead expense is indirect labor.

Operating profit

This discussion started with revenues, and, after one cost category, direct expenses, progressed to net revenues. From net revenues come a firm’s operating expenses – direct labor and the overhead labor & expense cost categories. Whatever money is still left is profit—at this point called "operating profit." This is the money a firm has generated from its operations, what is left from all its net revenues after it has paid every one of its people and all its other operating expenses. Operating profit, though, is not how much profit a firm ultimately makes.

Presuming a firm does make a profit, there are one minor and two major cost categories remaining. The minor one is called, simply, other income or loss. Usually not significant, it is more a technical category, just a place for accountants to record non-operations-related entries.

The two remaining major cost categories presume an operating profit and are only of interest if there is profit. They are bonuses and taxes. Bonuses are common in firms that have made healthy profits (but so, too, are taxes). Operating profits are the only thing that allows bonuses, and the only time a firm can complain about taxes is after it has made a profit.

Key performance indicators

"Metric" is a rather generic term, and a metric can be derived for almost anything measurable or quantifiable. Financial metrics, so-called because the metrics are derived from financial statements, are a principal means of monitoring operational activities. Yet just because something can be measured does not mean that it needs to be monitored.

Practice management books, surveys, and trend reports about the architecture industry are replete with financial metrics that can help firms benchmark themselves against industry averages. Nevertheless, only a select few of these provide the essential information managers at all levels of a firm need to monitor. The new jargon for these key metrics is “key performance indicators,” or KPIs.

What separates a KPI from other metrics are the following:

· It reflects actual progress towards an organizational goal.

· It monitors the performance level necessary for attaining an organizational goal.

· It is based on valid information to which managers have access.

· It is straightforwardly understandable.

· It has meaning at all organizational levels.

· It has underlying, corrective actions.

The following KPIs demonstrate basic financial relationships between the various income statement categories; monitoring them and taking timely corrective actions when necessary are essential for successfully managing a firm.

Operating profit rate

It can never be said enough: Profit is necessary. How much profit, though, is within the purview of the firm’s owners, and a target or goal is set. Nonetheless, since all other KPIs are related to achieving this goal, it dictates that a KPI related to operating profit is first.

To provide context and comparability, an operating profit rate target normally is established. It is calculated as:

operating profit/net revenue

Note the emphasis on net revenue rather than total revenue, the use of which provides comparability. However, unless a firm has profit centers, and full allocation of overhead to them, operating profit rate may only be an overall firm target.

The historic average is ±10%. However, there are firms that make much more than this. Then again, since 10% is an average, it also means that there are firms, unfortunately, that make less, including less than zero—in other words, losses.

Utilization rate

As discussed, a firm’s largest expenses are payroll and payroll related. As such, the most important managerial responsibilities involve efficiently and effectively utilizing its people. Utilization rate answers the question, “For all the dollars paid to people, how many of them actually go towards billable client projects?” There is not a firm that does not pay attention, in one way or another, to utilization. The KPI utilization rate is calculated as:

direct labor/total labor

All firms want their people to be spending the time for which they are being paid actively involved in some sort of productive work. Many firms seek to set utilization rate targets for individual employees, sometimes as high as 80%. (No one’s target rate can exceed 90% because vacation, holiday, and sick time, etc., generally accounts for ±10%.)

Nonetheless, it is a common misnomer that utilization rates are to be maximized. That is wrong—utilization rates need to be optimized! For the moment, disregard vacation, holiday, and sick time; these are part of each employee’s compensation. Think about marketing. There also are necessary and appropriate levels of training and continuing education—and marketing. Plus, there are necessary and appropriate levels of administrative activities—and marketing. It is obvious how not enough of each of these activities—especially marketing—will hurt a firm in the long term. In fact, many senior people within a firm may have utilization rate targets well below 50%, if not 0%, because much or most of their time is spent on marketing.

This KPI is used particularly for monitoring operating units of a firm; each unit can have a measurable utilization rate. It does not really consider dedicated administrative staff whose target utilization rates frequently are 0%. As such, the overall utilization rate for a firm may be optimized at just 60–65%, but utilization rates for individual units may be optimized at higher levels.

Net multiplier

Where utilization rate answered the question, “For all the dollars paid to people, how many of them actually go towards billable client projects?” the obvious next question is, “For each dollar that goes towards a billable client project, how many dollars does the firm get in return?” Whether it is called a net multiplier, a billing multiplier, or net service multiplier, it is calculated as:

net revenue/direct labor

Again, instead of total revenue, a firm’s—or even a project’s—net revenue is compared to direct labor.

Multipliers can—and should—be calculated, reported, and monitored right down to the project level, and then aggregated to the PM, department, etc., levels, as well as for the firm as a whole.

For decades before the days of computers, the rule-of-thumb was, “If a firm can bill out its people at three times what it pays them per hour, it ought to be able to make a profit.” Maybe not surprisingly, ±3.0 is still close to the historic industry average, although many firms or individual projects can earn much higher—or lower—net multipliers.

Payroll multiplier

The two KPIs previously presented are the most important for monitoring and managing operations. However, another KPI, the payroll multiplier, actually subsumes those two and provides a more important and comprehensive way of measuring and monitoring exactly what a firm gets in return for all of its labor costs. The payroll multiplier is calculated as:

net revenue/total labor

Note again the emphasis on net rather than total revenue, the use of which provides comparability at group, department, division, etc., levels, as well as the overall firm.

The payroll multiplier is more important and comprehensive because achieving a payroll multiplier target requires positive results for both the utilization rate and the net multiplier, which otherwise offset each other.

net multiplier = net revenue/direct labor

and:

utilization rate = direct labor/total labor

Multiplying the two together gives:

net rev/dir labor X dir labor/total labor

= net rev/dir labor X dir labor/total labor

= net revenue/total labor

which is the payroll multiplier.

Emphasizing either KPI over the other diminishes the other’s results and may actually cause “gaming” of the system, but the payroll multiplier catches it. People concerned about reaching their utilization rate target may put unnecessary extra time onto a project, increasing the project’s direct labor; however, more direct labor equally lowers the project’s net multiplier. Managers may try to increase a project’s net multiplier by restricting charges to it; decreasing direct labor equally increases indirect labor, and, therefore, the utilization rate. If there just are not enough projects on which people can work, the net multiplier remains acceptable, if the PM is running the project well but the department’s low utilization rate targets backlog or staffing levels as the problem.

The KPIs presented warrant attention because total labor costs, plus the cost of payroll-related expenses, comprise up to 75% of a firm’s total operating costs. As such, just by monitoring each department’s payroll multiplier and its components, net multiplier and utilization rate, managers are thereby monitoring the efficient and effective use of up to 75% of a firm’s total operating costs – KPIs and costs that can be monitored down to individual project and department levels.

Overhead rate

As presented, three cost categories – indirect labor, payroll-related indirect expenses, and other indirect expenses – are the components of a firm’s overhead. To pay for these expenses, a firm must charge enough for its services to cover both the direct labor put into its projects and its overhead. As such, another KPI is a firm’s overhead rate, which is:

total overhead/direct labor

This next statement may sound contrary to accepted belief: Monitoring a firm’s overhead rate is not as critical for monitoring and managing a firm as are the KPIs previously presented. That is because changes to the overhead rate, positive or negative, usually result from corresponding changes to the utilization rate. Indirect labor is the largest single component of overhead and varies widely because of staff utilization levels. Increases in indirect labor costs mean an equal increase in overhead; so, a decrease in the utilization rate probably means an increase in overhead.

However, if an increase in indirect labor is because of less project activity, the reduction in direct labor means each dollar of direct labor needs to support more dollars of overhead (a smaller denominator in the overhead rate equation). Further, higher indirect labor itself causes overhead to increase (a simultaneous increase in the numerator of the overhead rate equation). As such, the first place to look for any explanation for variances in the overhead rate is to look for changes in utilization rate.

The overhead rate is dependent on the utilization rate, which makes utilization rate a more important KPI.

Breakeven rate

Historic industry averages for overhead rates have averaged ±1.70 – with a great big ‟±.” In other words, for every $1.00 of direct labor costs incurred for a project, a firm also has another ±$1.70 in overhead costs. Further, it means that a firm has to realize ±$2.70 in fees to cover both the direct labor and the overhead costs in order to break even, thereby earning its name "breakeven rate," which is:

1 + overhead rate

The value of this KPI is strictly to quickly be able to compare it to a firm’s net multiplier; a higher net multiplier means the firm is making a profit; and lower net multiplier, a loss. Note that if a firm is achieving a historic average 3.00 net multiplier and realizing a historic average 2.70 breakeven rate, it also is achieving a historic average 10% operating profit rate.

Therefore, keep multipliers up, and utilization rates optimal—actions and activities that can be influenced each day by each person in a firm—so that everyone can earn bonuses, and complain about taxes.

About the contributor

Mike Webber started A/E Finance after years as a CFO. He works with A/E Principals and Boards on operations & financial analysis & systems, strategic planning, turnarounds, and interim assignments. He has been Chair of AIA Chicago's Practice Management Committee, an AIA/ACEC Peer Reviewer, and on ACEC's Management Practices Committee.

AIA collects and disseminates Best Practices as a service to AIA members without endorsement or recommendation. Appropriate use of the information provided is the responsibility of the reader.

Help build AIA Best Practices by contributing your experience. Contact us with your feedback or ideas for an article.